See this panel on Religion and Free Speech as part of our ongoing conversation on Free Speech and the Left

One afternoon last June, Salwan Momika, an Iraqi refugee living in Sweden, stepped in front of the largest Mosque in Sweden and lit several pages from the Quran on fire. Momika had sought and received a permit from the Swedish authorities for his provocative demonstration, and there were police monitoring the event.

The event, apparently involving two people, caused international uproar and condemnation from world leaders, especially in the Middle-East. It may affect Sweden’s prospects for entry into NATO, and both the Pope and Putin felt the need to weigh in.

This incident has been widely presented as a case of Sweden’s misguided support for free speech at the cost of insulting a minority. It should be noted that most of the reactions came from leaders of countries that are majority Muslim and have power structures based on Islamic law. It is important to remember that blasphemy laws are in place in countries where the dominant majority is imposing speech restrictions on weaker minorities.

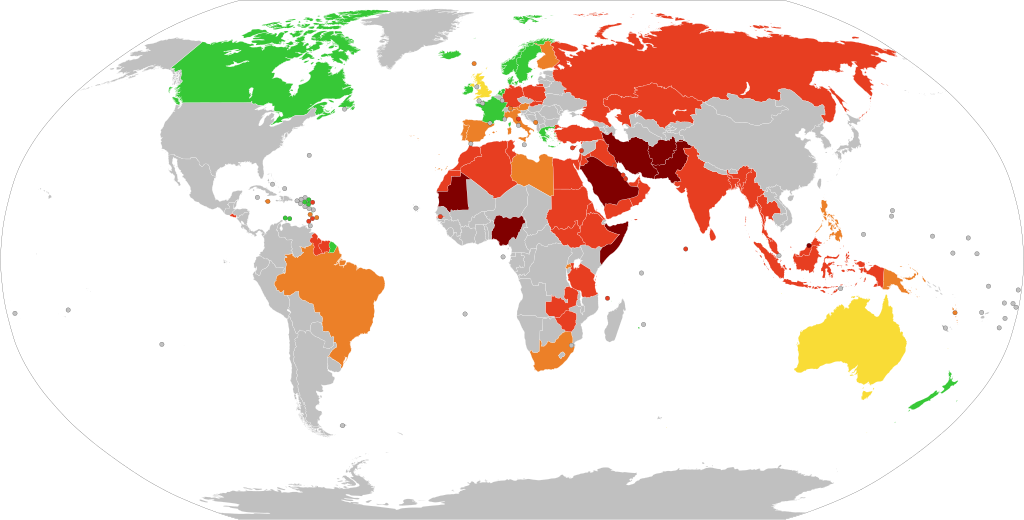

As recently as 2019, according to a Pew Research survey, 40% of the countries of the world, or 79 countries, still had blasphemy laws on the books. Seven countries still have death penalties for blasphemy—Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, Nigeria, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. See our earlier piece – Blasphemy – a notion that crystallizes so many of the issues around free speech.

No blasphemy law Repealed Local restrictions Fines and restrictions Prison sentences Death sentences

Conquistador, Blasphemy laws worldwide, CC BY-SA 4.0

This is in contrast to those countries in the West, like France and Germany, that have hate speech laws ostensibly to protect minorities. There is a widespread feeling, particularly in the West, that criticism of religion is a special category of speech that targets marginalized groups and should therefore be forbidden and possibly even outlawed.

The persistence of both blasphemy laws and hate speech laws highlights the confusion people have between laws that are founded on principles that can be generalized and applied consistently, and laws that are fashioned arbitrarily in deference to a particular cause, group or concern of the moment.

What is now widely considered hate speech against religion would have until very recently been standard criticism of religion among the left, part of a long, painful struggle by the weakest and most marginalized against religious domination—in particular against the Catholic Church which for centuries was the power center throughout Europe. It is easy to forget how religion used to rule over every aspect of our lives in the West.

The question remains as to whether criticism, or even mockery of religion is an act of bullying against a marginalized minority or one of the few ways available to loudly challenge the power of a dominant and oppressive point of view.

There is an odd exceptionalism in the West, and particularly among the woke left, that believes that only the West, and in particular people of one particular skin color, are the unique source of the world’s evils of racism, imperial domination or religious oppression. Often the word tolerance is invoked to discourage criticism or even mockery of religious doctrine. That is in part because of a mistaken assumption that such criticism is actually bullying of a weak minority.

The Quran burnings in Sweden bring out all these contradictions because it took place in Sweden, which is minority Muslim and could therefore be interpreted as ‘hate speech’ or bullying of a minority, but the act was a clear statement aimed at Muslims outside of Sweden, and has triggered angry reactions from powerful Muslim figures around the world.

A hard-wired truth about our human psyche is that along with strong religious beliefs seems to always come an equally strong need to have others agree with those beliefs, a need which is always in tension with another equally innate human drive—a desire to be free to arrive at one’s own opinions and to express them honestly. We need more nuanced conversations where all sides of the issue can be freely explored.